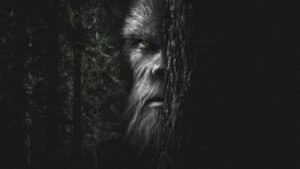

What Are Indigenous Bigfoot Beliefs?

October 2025 brought a powerful reminder that sasquatch stories existed long before modern America took interest. Oregon Public Broadcasting published extensive interviews with Columbia River tribal members about their relationship with the creature known as Bigfoot. Understanding indigenous bigfoot beliefs provides crucial context often missing from mainstream cryptid discussion.

Before sasquatch became a pop culture phenomenon, Native American societies maintained rich oral traditions about these beings. The creature we call Bigfoot carries different names across tribal languages, each reflecting unique cultural relationships. What western researchers treat as mystery, many indigenous communities regard as established knowledge.

Names Across Tribal Languages

The word sasquatch itself derives from indigenous origins that many enthusiasts overlook. Sasq’ets comes from Halq’emeylem spoken by the Stó:lō people in what is now British Columbia. Indigenous bigfoot beliefs shaped the very terminology researchers use today.

Columbia River Plateau tribes know the creature by names including Istiyehe and Stiyahama. Ichishkíin and Niimi’ipuutímt speakers from Yakama, Umatilla, Nez Perce, and Warm Springs communities each maintain their own traditions. Scholar Phil Cash Cash of Cayuse and Nez Perce heritage confirms that multiple names exist because relationships with this being run deep.

These linguistic variations indicate independent cultural development rather than borrowed legends. Separate communities across vast distances developed distinct traditions about similar beings. Indigenous bigfoot beliefs emerged organically from lived experience across generations.

Spiritual Dimensions Often Ignored

Western researchers typically approach sasquatch as a biological question about undiscovered primates. Indigenous perspectives frequently emphasize spiritual dimensions that scientific frameworks dismiss. World champion jingle dancer Acosia Red Elk of Umatilla, Cayuse, and Walla Walla heritage describes Bigfoot as a protector.

Her community always spoke of how Bigfoot watched over her people according to Red Elk. This protective relationship differs fundamentally from the monster narrative popular culture promotes. Tribal traditions position these beings as relatives rather than threats requiring proof.

Guardian spirit traditions predate European contact by centuries at minimum. Indigenous communities did not need blurry photographs or footprint casts to know these beings existed. Oral histories passed through countless generations carried knowledge western science now struggles to validate.

Why These Perspectives Matter

Researchers ignoring indigenous bigfoot beliefs operate with incomplete information affecting their conclusions. Cultural knowledge accumulated over millennia deserves consideration alongside recent sighting reports. First Nations peoples observed these forests far longer than any modern investigation.

Behavioral patterns described in tribal traditions often align with contemporary witness accounts surprisingly well. Descriptions of intelligence, elusiveness, and territorial awareness appear consistently across sources. Perhaps indigenous observers understood sasquatch behavior better than researchers realize.

Dismissing spiritual interpretations as primitive superstition reflects cultural bias rather than scientific rigor. Indigenous communities maintain sophisticated understanding of their environments developed through direct relationship. Their perspectives on sasquatch deserve the same respect accorded to any expert knowledge system.

The Commodification Problem

Bigfoot has become commercial property across the Pacific Northwest, appearing on everything from bumper stickers to street corner statues. This commodification troubles many indigenous community members who view sasquatch as sacred. Indigenous bigfoot beliefs become trivialized when reduced to tourist merchandise.

Mainstream fascination with sasquatch rarely acknowledges cultural origins of these traditions. Enthusiasts search forests hoping to capture evidence without understanding whose land they explore. Indigenous perspectives remind us that sasquatch stories belong to specific peoples with ongoing relationships.

Respectful research would center indigenous voices rather than treating their knowledge as footnotes. Communities willing to share traditions deserve recognition as primary sources. Perhaps collaboration between researchers and tribal knowledge keepers could advance understanding significantly.

Implications for Serious Investigation

Indigenous bigfoot beliefs suggest these beings possess intelligence and spiritual significance beyond simple animal classification. If sasquatch represents something more than undiscovered ape, biological frameworks may prove insufficient. Researchers open to broader interpretations might discover insights others miss.

Cultural continuity across thousands of years indicates sustained presence rather than recent emergence. Whatever generates these traditions has apparently coexisted with human communities since time immemorial. These perspectives point toward deep history western science has barely begun exploring.

Conclusions for Researchers

Sasquatch investigation benefits from humility about what western science does not know. Indigenous communities maintained sophisticated relationships with these beings while European settlers dismissed them as fantasy. Perhaps the knowledge we seek already exists within traditions too often ignored.

Those forests belong to peoples who knew them long before us. Their stories deserve our attention and respect.

Listening might teach us more than searching ever could.